In 1994, when we first opened the Clay Coyote Pottery on the farm, my mom, Betsy Price, and her business partner, Tom Wirt, were just getting started making pots for a living. I was only fourteen and my brother was one year younger, and we were building character through free labor.

Tom and Betsy were so busy making pots and going to shows every weekend, so that same year we opened the showroom in the old pump house. The floor was wooden and dusty and there was a hole where the pump went. There was also an old cast iron aga stove and a potbelly stove in the corner. We added shelves to the walls and put pots out with a self serve cash box. It was rustic and inviting.

Customers still talk about the self serve showroom to this day. It was a time of great trust. There was even an old knuckle buster credit card machine and people would rub out their card numbers and leave payment. It was amazing.

We’ve come a long way since then, adding a Gallery in 2002. And in 2016, Ian, my husband, and I, moved from Harlem, NYC to Hutchinson and bought the business. Tom retired from production pottery and moved to a small house in town. My mom stayed on with us through the transition and continues to love her time in the Gallery and Studio.

It is not lost on me that Betsy and Tom uprooted their lives to move from a city to the country, and twenty-two years later we made a similar move.

Since taking over, we’ve hired a team of potters to continue our family’s Chef’s Line and Baking Line of cookware pottery. We still make more than 7,000 pots a year and we’re growing.

***

A Little More History

When thinking about cooking with clay, you have to start with the original shepherd of the American clay pot cooking movement, Paula Wolfert. She not only literally wrote the book on clay, she also played a pivotal role in the pots we’re making to this day.

Paula’s book, Mediterranean Clay Pot Cooking, written in 2009, is a cross cultural guide to acquiring, using, and caring for your clay cookware. Its pages are filled with recipes from Paula’s tour to the heart of some of the most culinary rich places on the globe. And it’s a lesson in clay history that everyone should read.

My mom, Betsy, and her business partner, Tom, first were introduced to Paula in the late 1990s. She first reached out to them for a couscous colander, then a vessel for making homemade vinegar, then she commissioned a French cassole to hold her traditional 22-cup cassoulet recipe, and then one day she asked if they’d ever considered making flameware, a pot that could go over direct heat.

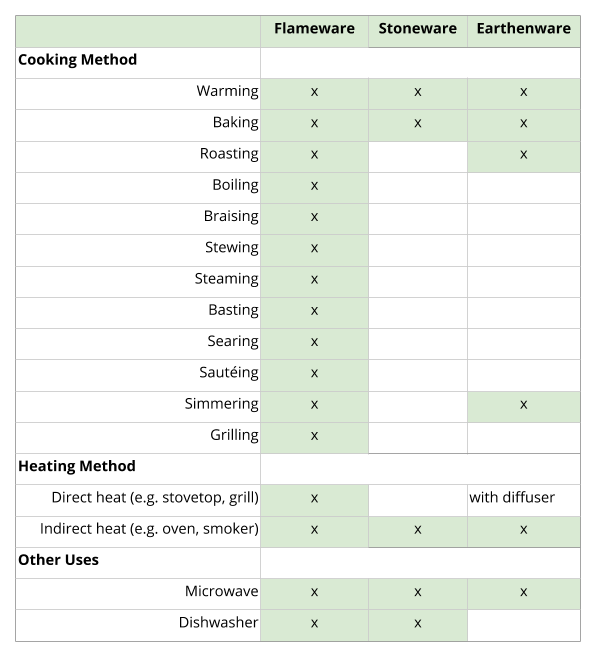

We’ll spend a lot of time talking about direct heat and indirect heat pots and the different purposes for each, but for a minute we’ll stay on the story of how the Clay Coyote came to flameware.

Tom began researching clays, and reaching out to the flameware experts across the country, notably Bill Sax from Massachusetts who’d been working with flameware for more than two decades and on the verge of retirement, and Terry Silverman, from New Hampshire, whose business is called The Pottery Works. Terry is still making and selling pots today and they are great additions to your clay kitchen collection.

While Tom focused on modifying Bill’s recipe to fit our forms and firing techniques, Betsy was at work on the glaze recipe. Because not only did the clay body have to expand and contract with the high heat and temperature changes, so did the glaze. They worked with experts like Ron Roy of Canada to test the glazes for food safety. And went into the kitchen over and over with every new batch of pots from the kiln.

After two years of trial and error, cracks, and yes, some explosions (just ask Ann), they had found a glaze and clay combo that worked. That was more than a decade ago, many of the amazing Clay Coyote pots have come from Paula’s challenges over the years, many were born to solve cooking conundrums, many are traditional pots from history that deserve a place in today’s modern kitchens, and many more have come from the suggestions of our dedicated customers along the way.

The history of clay pot cooking is long, filled with origins of necessity and access to resources. The first clay pots were prehistoric, many think the first pots date back to 14,000 BC. They were hand formed tools to feed families. On one of my recent travels to Greece, I saw a pottery wheel dated 1600-1450 BC. I was in awe.

Today, the Cooking with Clay movement is stronger than ever, there’s an amazing group on Facebook just dedicated to the pots, the process, and recipe sharing. At the time of writing, the group has more than 1,400 members who are passionate about all things clay cooking.

There are thousands of potters around the globe making different kinds of clay pots that you can put to work in your kitchen. From skillets, casseroles, pie plates, bacon cookers, and even coffee pour overs, potters continue to push the boundaries of clay functionality. It’s inspiring to think of all the places potters may take us for the next 14,000 years.

***

Overview Of Clay Pots

Overview Of Clay Pots

Most of the pottery in day-to-day life is stoneware, earthenware, porcelain, or terracotta. It can be unglazed or glazed. If glazed, it’s normally fired at least twice, but there are exceptions where some potters have come up with a single firing process. The clay body, that is the main material. Clay can be dug up and used right from the ground, there are potters who use wild, or native clay. One of my favorite plates is from wild clay in North Carolina, it’s dark, gritty, and primitive, while also modern. The other way that most potters get clay is by mixing batches of different minerals together to form bodies.

On top of the clay bodies potters add different glazes to create the final piece, bright colors, earthy tones, matte, shiny, organic combos that move and flow together to create new glaze reactions. Glaze, however, is essentially glass, and we all know that glass doesn’t like to expand or contract (think about that one time you left a bottle of pop or wine in the freezer … oops).

Stoneware pottery is fired to at least 2000F which makes the clay very hard and nonporous. Unfortunately, in the firing process there is some crystalline silica residue, and these silica crystals will expand and contract when heated and cooled. These pots cannot take the expansion and contraction and will crack.

Pots that don’t need to expand and contract rapidly are great for daily functionality like plates, bowls, mugs, vases, spoon rests, serving bowls, and yes, even casserole dishes. It’s not that these clay bodies can’t change temperature, they just can’t do it rapidly. So baking in the oven, yes. On the grill with flames char-broiling the bottom, no.

There are different things that can be done to formulate clay bodies and they can be tested with a precision instrument called a dilatometer.

Most stoneware, earthenware, and porcelain pottery can be used in the oven, microwave, and dishwasher because even though they all create heating and cooling environments the pottery isn’t being shocked.

In the clay pot cooking world you will come across vessels from other parts of the world that are advertised as flameproof. Many of these pots are unglazed and come with care instructions, like soaking and curing, although these pots will remain somewhat porous. The more popular imports are made of micaceous clay fired to around 1200F. The clay is indigenous to certain parts of the world and if you add some of these to your clay pot kitchen you will find many recipes that specifically recommend unglazed pots. They were also normally intended for use with charcoal or briquette fires. If you were to use them over a stovetop flame, we’d still recommend using a heat diffuser (these are sold for $15-50). It’s not a bad investment for your clay kitchen toolkit because heat diffusers are interchangeable for various pottery shapes and sizes. And if you are ever unsure about the pottery origins you can use it with a better-safe-than-sorry motto.

If you’re looking for clay that can withstand direct heat, you want flameware. It’s a combination of clay, silica, and a lithium ore like spodumene. Flameware is fired up to 2387F or more and in the process the ore goes through an expansion process that later prevents the clay body from reacting to rapid temperature changes. Just like the other types of pottery, the clay body dictates the types and behaviors of the glaze. A glaze that you’d use on stoneware plates cannot be used on a flameware skillet.

There are a few potters across the USA making and mass marketing flameware pottery. We all have different aesthetics, different clay recipes, different glaze formulations, and different functionality. Personally, I believe that in the clay community we’re all stronger together. My clay kitchen collection is made of of the artwork of more than a hundred different potters (yes, really, much to my husband’s dismay).

***

When the Clay Coyote first began more than two decades ago, the vision was simple: create a space where people come to buy handmade, functional, and affordable pottery in central Minnesota.

When the Clay Coyote first began more than two decades ago, the vision was simple: create a space where people come to buy handmade, functional, and affordable pottery in central Minnesota.

Those words still read true today at the Clay Coyote under the management of Morgan (Betsy’s daughter) and Ian Baum, the second generation of the Clay Coyote.

Here at the Clay Coyote we promise to continue to build on the amazing foundation that Tom and Betsy created.

-Morgan & The Coyotes