Most of the pottery in day-to-day life is stoneware, earthenware, porcelain, or terracotta. It can be unglazed or glazed. If glazed, it’s normally fired at least twice, but there are exceptions where some potters have come up with a single firing process. The clay body, that is the main material. Clay can be dug up and used right from the ground, there are potters who use wild, or native clay. One of my favorite plates is from wild clay in North Carolina, it’s dark, gritty, and primitive, while also modern. The other way that most potters get clay is by mixing batches of different minerals together to form bodies.

On top of the clay bodies potters add different glazes to create the final piece, bright colors, earthy tones, matte, shiny, organic combos that move and flow together to create new glaze reactions. Glaze, however, is essentially glass, and we all know that glass doesn’t like to expand or contract (think about that one time you left a bottle of pop or wine in the freezer … oops).

Stoneware pottery is fired to at least 2000F which makes the clay very hard and nonporous. Unfortunately, in the firing process there is some crystalline silica residue, and these silica crystals will expand and contract when heated and cooled. These pots cannot take the expansion and contraction and will crack.

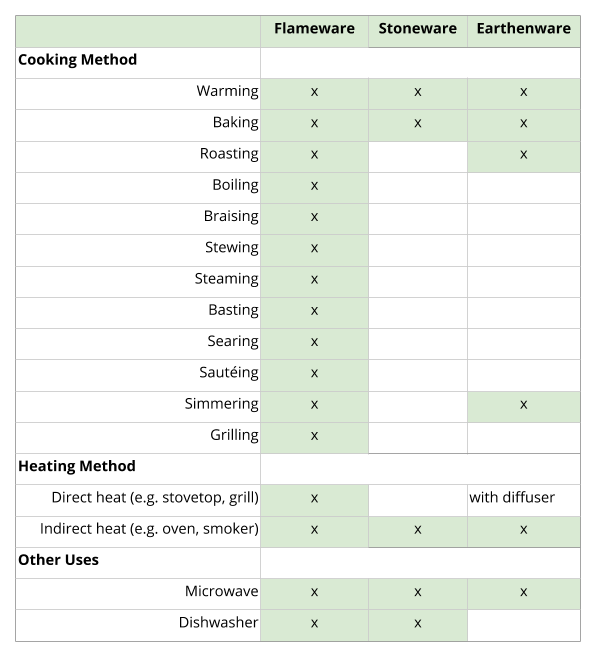

Pots that don’t need to expand and contract rapidly are great for daily functionality like plates, bowls, mugs, vases, spoon rests, serving bowls, and yes, even casserole dishes. It’s not that these clay bodies can’t change temperature, they just can’t do it rapidly. So baking in the oven, yes. On the grill with flames char-broiling the bottom, no.

We recommend our stoneware up to 400F, some recipes that call for 450-500F can still be made in our pottery because clay is an insulator and holds the heat.

There are different things that can be done to formulate clay bodies and they can be tested with a precision instrument called a dilatometer.

Most stoneware, earthenware, and porcelain pottery can be used in the oven, microwave, and dishwasher because even though they all create heating and cooling environments the pottery isn’t being shocked.

In the clay pot cooking world you will come across vessels from other parts of the world that are advertised as flameproof. Many of these pots are unglazed and come with care instructions, like soaking and curing, although these pots will remain somewhat porous. The more popular imports are made of micaceous clay fired to around 1200F. The clay is indigenous to certain parts of the world and if you add some of these to your clay pot kitchen you will find many recipes that specifically recommend unglazed pots. They were also normally intended for use with charcoal or briquette fires. If you were to use them over a stovetop flame, we’d still recommend using a heat diffuser (these are sold for $15-50). It’s not a bad investment for your clay kitchen toolkit because heat diffusers are interchangeable for various pottery shapes and sizes. And if you are ever unsure about the pottery origins you can use it with a better-safe-than-sorry motto.

If you’re looking for clay that can withstand direct heat, you want flameware. It’s a combination of clay, silica, and a lithium ore like spodumene. Flameware is fired up to 2387F or more and in the process the ore goes through an expansion process that later prevents the clay body from reacting to rapid temperature changes. Just like the other types of pottery, the clay body dictates the types and behaviors of the glaze. A glaze that you’d use on stoneware plates cannot be used on a flameware skillet.

There are a few potters across the USA making and mass marketing flameware pottery. We all have different aesthetics, different clay recipes, different glaze formulations, and different functionality. Personally, I believe that in the clay community we’re all stronger together. My clay kitchen collection is made of the artwork of more than a hundred different potters (yes, really, much to my husband’s dismay).

See our Flameware Pottery